After the Noor Ouarzazate Project, Abengoa, a Spanish energy company, has signed an agreement with the Moroccan government to build a seawater desalination plant powered by solar energy. A promising technology for many countries facing drinking water shortages.

At a time when the ecological issue has never been so crucial, the Spanish industrial group Abengoa, specialized in the field of energy, has signed an agreement with the Moroccan government. This includes the construction of the world’s largest seawater desalination plant, operated mainly with solar energy.

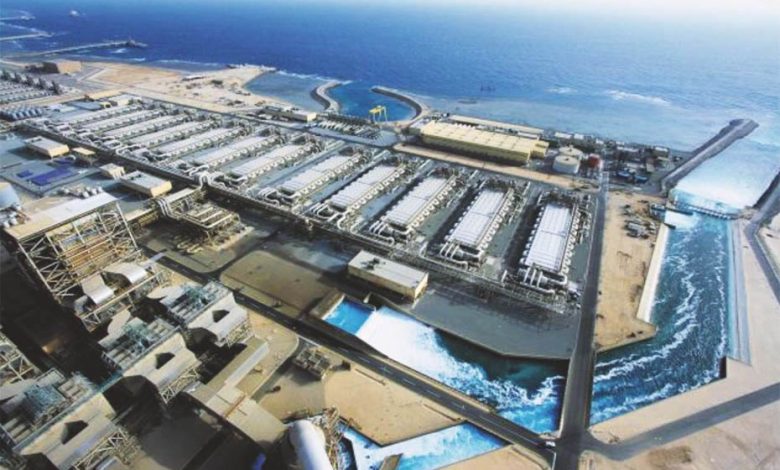

Once completed, this plant should start producing nearly 275,000 cubic meters of water per day – 150,000 for food consumption and 125,000 to irrigate the 13,600 hectares of plantations near Agadir, in the southwest of the country – ideally reaching its maximum capacity of 450,000 per day. Abengoa will be responsible for the development, construction, and maintenance of the plant for at least 27 years.

Water desalination techniques

Two processes currently exist to desalinate seawater: thermal and reverse osmosis. The first method is to extract fresh water from seawater by heating the mixture. While the water will condense, the salt and impurities will remain in solid form. The water vapors are then placed in a sealed tube to be cooled with seawater and transformed into a liquid and pure water. The second – the one used by Abengoa in the case of the Moroccan project – consists of filtering seawater using powerful high-pressure pumps, allowing only the water molecules to pass through.

It is the first technology that is most widespread in the Middle East, particularly in Saudi Arabia, where thermal plants are powered by waste heat generated by oil-fired power plants. A process that makes energy almost free of charge on these lands rich in fossil fuels and close to the sea.

For the major oil countries, it is therefore much easier to use solar energy, as Morocco does or as many other Central African countries could do. It would be essential to install such technology, allowing both seawater and polluted river water to be treated. Nevertheless, this type of installation remains very expensive compared to the extraction of drinking water from other sources.

A key challenge

The signing of such a project remains a good sign for renewable energy advocates, as the Moroccan government has announced that the plant will be powered by the Noor Ouarzazate solar power plant.

This type of seawater desalination plant is quite rare, with only 21,000 such facilities worldwide – mostly in the Middle East. Less than 1% of the world’s population depends on it for drinking water. Yet the stakes are high, given these two figures: nearly 4 billion people face shortages of drinking water, while 97.5% of the total body of water on earth is salty.

With an average consumption – direct and indirect, including agriculture and industrial use – of 3.8 cubic meters of water per person every day, the Abengoa plant will be able to meet the needs of nearly 72,500 people.

Now that there are nearly 7.5 billion people on this planet, it would take nearly 104,000 such plants to provide drinking water for everyone. When we look at the various problems of access to drinking water, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, this solution could be most beneficial.

What uses on a global scale?

But there is a major problem with the generalization of this process: cost. Already because they are expensive facilities, but also because, for some people in countries affected by water crises, water, even at a price considered low for many, can become a huge burden.

The Jülich Solar-Institute in Germany has developed a small distillation to produce 10,000 liters of clean water per day, offered at a price of 2 cents per liter. Only one person needs 5 liters of water per day. For example, Klemens Schwarzer, the German scientist in charge of the project, estimates from DW that « if we consider a family of eight people – two adults and six children – that makes 40 liters, or 80 cents a day. For an African family earning only a few euros a day, this is far too much. »

It is difficult to judge which solution would be the right one: it will surely have to wait for the drop-in installation costs and the arrival of a real (common?) political will to solve the drinking water problem in some parts of the world.